A Handicapped Teacher Has Something Special to Offer — Especially in a Recently Mainstreamed Classroom

by Vincent Rogers

From Phi Delta Kappan, Sept. 1979, vol. 61, no. 1

It’s 8 a.m. — a cool, bright Connecticut September morning. The air is light and alive with a hint of fall. It is the first day of school.

The brown Saab pulls up slowly, carefully, to the school’s ramped entrance. The car stops and an attractive, dark-haired, modishly dressed woman in her early fifties opens the door. Deliberately, laboriously, yet surely she works herself out of her seat and stands next to the car. She stops for a moment to rest and gather her strength, then takes a cautious step forward. Using the car as a railing, she walks slowly toward the entrance, which is, for her, a challenging 15 or 20 feet away. Once inside the door, she sits down in a waiting battery-powered vehicle called an Amigo, shifts it into “forward,” and drives down the wide, still-empty corridor toward her primary-grade classroom at a speed of five miles per hour.

Chris Rogers is a teacher — one of the best in the district if the opinions of parents and colleagues mean anything. She is also wife, companion, advisor, and confidante of her hyperactive college professor husband, as well as mother and special friend to three grown children.

Chris has multiple sclerosis.

The diagnosis was made about five years ago, but the symptoms were there long before that: fatigue, spasticity, muscles that simply won’t do what the mind tells them to do. M.S. is a disease of the central nervous system. Slowly the body loses its ability to transmit messages from the brain to the muscles that control locomotion and other functions. While considerable research is under way, at the moment there is no cure.

Teaching young children is hard, demanding work for even the most active, healthy young adult. To teach and teach well with M.S. demonstrates courage, tenacity, and commitment far out of the ordinary.

When M.S. strikes, lifelong habits and activities are changed; daily routines must be modified. The victim not only has to make these adjustments but worries constantly about her adequacy as a person — in this case, as a wife, mother, and homemaker.

For many handicapped people it is enough of a challenge simply to work out a reasonable solution to the problems of everyday living. Chris wasn’t satisfied with that. It isn’t enough for her. So she adds the enormous responsibility of continuing her role as teacher of a lively group of 20 or more 6- and 7-year-old children.

Teaching young children is hard, demanding work for even the most active, healthy young adult. To teach and teach well with M.S. demonstrates courage, tenacity, and commitment far out of the ordinary.

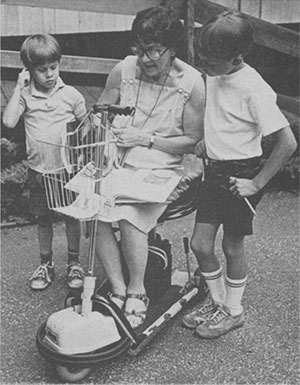

Chris’s Amigo is of course a great help. Psychologically, it is far superior to a wheelchair. It is more like a mini-motor scooter, yellow, with chrome handlebars, brake, and accelerator. It is narrow enough to go just about anywhere, and children of all ages love it.

Chris’s school day includes virtually every activity that any other teacher would be expected to carry out. Her personalized reading program runs very smoothly indeed, and her children are often among the school’s best readers. She has an active art center at which three or four children are always working, a housekeeping corner, and a math and science center as well. A former dancer, she offers spectacularly successful creative dance lessons, even though she conducts them from her Amigo.

As one might expect; Chris is especially sensitive to the handicapped children who were recently mainstreamed into her school. Her relationships with them are warm, accepting, and encouraging, and she serves as a living and successful model to those children who are in various ways different from their classmates.

The “normal” children, too, profit from having Chris as a teacher. From their point of view, she isn’t handicapped; she is simply that “lucky lady who drives the wagon.” The greatest reward for any of them is a ride on the Amigo — and they are learning that people with physical handicaps aren’t really that different as people, once you get to know them.

I suspect the same valuable insights are being learned by others who come in contact with Chris, including fellow teachers, parents, cooks, janitors, principals, school psychologists, student teachers, and the superintendent of schools.

We often think of courage in battlefield terms — the courage to face death under fire, to stay with the sinking ship, to rescue a fallen comrade. There is also the quiet, less spectacular courage of Chris Rogers and others like her who must claw, scratch, and struggle every day to do those things most of us take for granted. She does them without complaint, tenderly and warmly, and she does them well.

This article originally appeared in the September 1979 edition of Phi Delta Kappan.

Chris Rogers, wife of author Vincent Rogers, passed away in 1979.